So you’re you, yes? A person of conservative or traditional or simply unloony views walking your campus with your head in...

Heroes and Victims in Modernist Memorials

This commentary appears in the Winter 2014 issue of Modern Age. To subscribe now, go here.

The decades preceding the French Revolution witnessed the cultural upheaval brought on in much of Europe by the simultaneous ascendancy of natural science, historical and archeological inquiry, and romantic sentiment. At that time, leading architects began to search for first principles that would strip away the detested encrustations of baroque and rococo. Seeking new sources of inspiration, they were led back in time—from the Coliseum and Pantheon in Rome, to archaic Greek temples in southern Italy, and still further back to the Egyptian pyramids and architecture’s beginnings.

That romantic and inevitably paradoxical quest for a primordial architecture, an architecture of new beginnings, has largely defined the modernist project, not least where the design of memorials is concerned. In our day, however, the classical tradition usually has little or no purchase on the creative imagination, a situation very different from the late eighteenth century. And because nothing by way of a modernist canon or set of normative forms and conventions has emerged to take that tradition’s place, our civic art has become increasingly dysfunctional since the Depression.

Still, the new Four Freedoms Park in New York City is one of the very best modernist memorials we have or are ever likely to have. Designed by the celebrated architect Louis I. Kahn (1901–1974), whose most notable works include the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, it was dedicated in October 2012 as a memorial to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The memorial is beautifully situated at the southern tip of Roosevelt Island, in the middle of the East River.

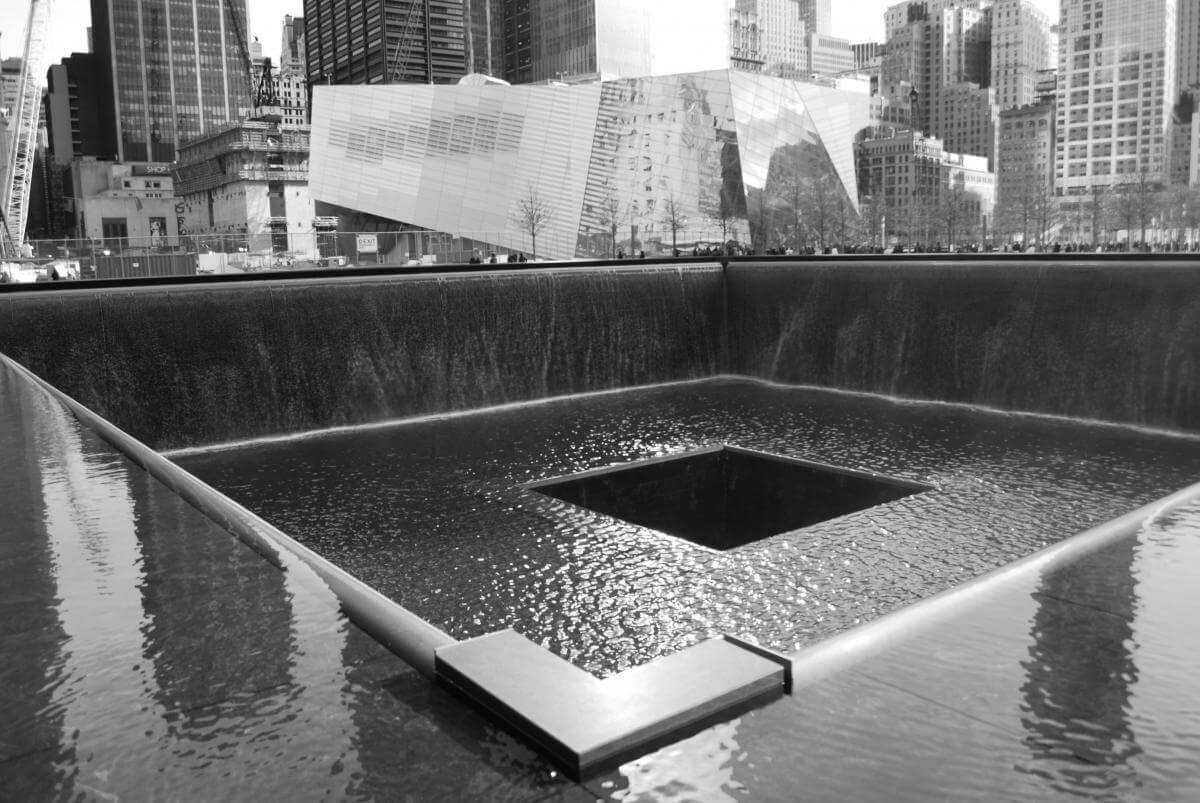

Among other things, Four Freedoms Park strikes a welcome contrast to the watery abysses of the National September 11 Memorial and Museum at the World Trade Center site, which opened on the tenth anniversary of the terrorist atrocity. The 9/11 Memorial is an excellent example of the depths (figurative as well as literal) civic art can reach in the absence of traditional norms. Yet, as we will see, it represents a variation on a romantic theme with a very specific eighteenth-century pedigree. This is also the case with Four Freedoms Park.

The park takes its name from FDR’s historic 1941 State of the Union address. Kahn’s design was completed shortly before his death in 1974 but put on hold amid Gotham’s financial crisis. Only in 2010 did construction of the $53 million, four-acre memorial get underway. Kahn, who had a penchant for speaking of his work in mystical terms, explained the park’s conceptual genesis as an epiphany of sorts: “I had this thought that a memorial should be a room and a garden. Why did I want a room and a garden? I just chose it to be the point of departure. The garden is somehow a personal nature, a personal kind of control of nature, a gathering of nature. And the room was the beginning of architecture.”

The solipsistic exegesis notwithstanding, there is a decidedly impersonal formality to Four Freedoms Park. Kahn’s memorial design was influenced by the stripped classicism his illustrious teacher, Paul Philippe Cret, deployed in works such as the Federal Reserve’s Eccles Building in Washington (1937) and the Eternal Light Peace Memorial at Gettysburg (1938). Kahn’s garden is a spacious terrace in the shape of a truncated “V” that slopes gently downward as it tapers, in line with Roosevelt Island’s footprint, toward the court in front of the open-air room. (Landscape architect Harriet Pattison collaborated with Kahn on the garden’s design.) The terrace is approached via a broad flight of steps monumental in scale, and each arm of the “V” is lined with allées of paired linden trees that gird the central lawn. On each flank of the terrace, ramps running parallel to it tilt upward from the park’s entrance plaza to the court in front of the room. The vertically tapered retaining walls separating terrace and ramps are steeply battered, and beyond the ramps riprap runs along the water’s edge. Architectural and paving elements were fabricated from a luminous granite.

The court features a freestanding rectilinear alcove harboring an oversize bronze bust of FDR, modeled from life by Jo Davidson (1883–1952). The excerpt from the Four Freedoms speech inscribed on the alcove’s southern face is the centerpiece of the room, which is largely enclosed by thirty-six-ton blocks twelve feet tall. The room’s southern end, however, offers an open view both down the river and also over to Manhattan and the United Nations complex and to Queens. The river’s rapid tidal flow considerably intensifies the dramatic setting.

And yet the serious limitations of the memorial’s formal vocabulary are readily evident. Leaving aside the portrait bust, the trees, and the circular tree planters, Kahn’s memorial design suffers from a tyranny of straight lines that gives it a rigid, even stilted, feel. The grand staircase inevitably creates the expectation of a powerful architectural presence at the summit, but instead one encounters the trees and grass and the inclined, tapered terrace’s tunnel-vision effect, which simply emphasizes the weakness of the vista’s termination by the alcove with the portrait bust.

In other words, the steps end up serving as a processional prelude to a letdown. This is because Kahn has essentially given us a temple precinct without a temple or anything like an adequate substitute. The garden’s terminated vista would have been well served by an emphatically vertical mass with a prominent sculptural element—a mass tailored to the river’s urban scale, not just the parochial scale of the memorial site itself. It’s a shame that Kahn, along with the memorial project’s original sponsor, the Four Freedoms Foundation, and city and state officials, ignored the precedent of the Statue of Liberty and the way it galvanizes the vast expanse of New York Harbor. But of course we live in an age in which civic art’s horizons have been drastically constricted.

The portrait bust is a disappointment in its own right. The soft modeling lacks rigor and the characterization is feeble. Maybe there just wasn’t a sculptor around who could do FDR justice. Still, Davidson’s portrait provides a much-needed formal counterpoint to Kahn’s architectural vocabulary, whose limitations are particularly conspicuous in the room. Here one encounters a stark monotony of right angles as well as straight lines and flat, completely unornamented surfaces in the massive upright blocks, the two long bench slabs, and the paving stones. Very much in line with that romantic eighteenth-century quest, Kahn sought to evoke the beginnings of architecture—“when the wall parted and the column became”—by specifying one-inch spaces between the upright blocks that are appreciably wider than the usual masonry joint but hardly wide enough to give the uninformed visitor a clue as to his intent.

These openings and the deep shadow lines they generate wind up making a jerry-built impression that is distracting. No question, the interplay of light and shade in architecture is essential. And ornament exists precisely to modulate the play of light and shade in a harmonious manner while providing a figurative contrast to the abstract elements of a given architectural design. Kahn’s notion that architecture could be reduced to a mystical essence in which ornament was superfluous proves seriously defective at this memorial.

The good news is that Four Freedoms Park as a whole is endowed with a welcome legibility. It doesn’t sprawl, conceptually or spatially, and in this sense it is the direct opposite of the lamentably labyrinthine and episodic Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial (1997) in Washington. Four Freedoms Park also retains a significant vestige of classical decorum, with the riprap-strewn perimeter expressing its proximity to the turbulent forces of nature while the memorial itself occupies a more formal, dignified plane. Needless to say, Kahn had architecture’s sacramental origins very much in mind when he designed the park. He aspired to enshrine FDR’s memory, not his own, and it shows. How very different is Frank Gehry’s bloated, histrionic design for an Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, which has run into serious opposition and, we may hope, will not be carried out.

While Kahn sought to convey an ideal sense of life at Four Freedoms Park, his reductive architectural forms invite comparison with Maya Lin’s minimalist Vietnam Veterans Memorial (1982). Lin’s design, which is of course devoid of any figurative element whatsoever, is better resolved insofar as it unfolds more vividly, with her chevron-shaped black granite wall gradually rising above you and immersing you in its lengthening panels of names of the dead as you descend to its vertex.

But the wall only encompasses death and the magnitude of loss that resulted from the Vietnam War. Nothing transcends that loss, which is the reason her dark wall is embedded in the earth. It remains an open question how much power it will retain—as a memorial, as opposed to an eye-catching exercise in Earth Art—after the memory of the war and its dead has faded. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, the memorial’s sponsor, is in the process of raising $85 million for a 35,000-square-foot multimedia “education center,” to include a photographic “wall of faces” of the dead. This underground facility will be situated in the vicinity of the Vietnam and Lincoln Memorials. Think of it as an exercise in commemorative mission creep.

The memorial at the World Trade Center raises the same question in relation to 9/11. Families of the victims insisted that the square footprints of the destroyed twin towers be retained. Disastrously, the resulting cavities—each thirty feet deep, nearly an acre in extent, and situated on a skewed diagonal in relation to the other—wound up constituting the heart and soul of the memorial. Except for their concrete floors, the cavities are clad in dark granite and fed by roaring waterfalls spanning their perimeters. Bronze panels bearing the names of the nearly three thousand people who lost their lives at Ground Zero, the Pentagon, and near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, gird the cavities’ parapets. Behind the panels the water is forced through tiny runnels so as to fall in textured sheets; upon reaching the bottom it pours into large square holes in the middle of each cavity floor. And it’s gone—just like the lives lost on 9/11. The title that architect Michael Arad gave his original competition-winning design, Reflecting Absence, says it all. (The title also refers to the idea of the cavities as reflecting pools.)

The 9/11 Memorial precinct, which occupies half of the sixteen-acre World Trade Center site, also includes a stark plaza designed by Arad’s like-minded collaborator Peter Walker. Here we have another exercise in rectilinearity—right down to the lampposts (or maybe one should say lamp sticks)—with some four hundred swamp white oaks providing the indispensable relief. But that relief is minimal indeed during the chilly months when the leaves are off the trees. Haphazardly framed by a motley array of tall buildings, including One World Trade Center (formerly dubbed the Freedom Tower), into which occupants will soon be moving, the memorial precinct conveys no sense of its commemorative purpose when you enter it from the security area. Before the waterfalls’ din registers, before the name panels become distinct, the twin cavities’ parapets might as well enclose skating rinks.

The plaza’s only significant architectural feature is the entrance pavilion for the 9/11 Memorial Museum, which takes up no less than 110,000 square feet nearly seventy feet below ground and is scheduled to open in the spring of 2014. The pavilion is an obnoxious deconstructionist agglomeration of faceted shapes designed by a trendy Norwegian office, Snøhetta. It would make a dandy gallery for art-world wunderkinder du jour.

Kahn’s Four Freedoms Park basically retains classicism’s qualitative focus—its concern with the distillation of human experience into symbolic, ideal form. Lin’s wall, however, signals a transition to a reliance on quantity by way of its lengthening panels of names, though her wall’s vertex does endow it with a focus, a measure of vertical integration, and a message about the mortal toll taken by the Vietnam War. Where’s the center of gravity at the 9/11 Memorial? There isn’t any. But the reliance on quantity has deepened, as manifest in the display of victims’ names but much more conspicuously in the size of the twin cavities, the Niagara-like volume of water pouring into them, and the volume of sound that generates.

This preoccupation with magnitude, and also with rudimentary geometric forms, has its roots in the exquisitely rendered architectural reveries of the Frenchman Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728–1799). The Egyptian pyramids served as inspiration for these reveries, which were never built for the simple reason that they were unbuildable. Rather, they were intended to overwhelm Boullée’s public with notions of the Sublime. Sublimity, of course, had become the romantic vehicle for the feelings of fear and awe once inspired by religion, whose status among educated people had been undermined by the triumphant progress of science. Fittingly, one of Boullée’s most memorable designs was a gigantic spherical mausoleum for Newton.

Arad’s 9/11 Memorial, however, inverts Boullée because it basically consists of a pair of very big holes in the ground—in other words, negative rather than positive forms. But his quixotic attempt at a minimalist sublimity is obvious. Lin’s wall, for its part, is basically a thin masonry veneer on a large geometric cut or indentation in the landscape. (Lin once likened her design concept to “a wound in the earth that is slowly healing.”) So her memorial, too, is an essentially negative form. Hence its antimonumental character. It’s also worth noting that as a juror in the 9/11 Memorial competition in 2003, Lin is known to have strongly supported Arad’s winning entry.

The quantitative drift is a leitmotif in recent memorials, and it has been reinforced by a thematic shift. Kahn was commemorating a hero, whereas Lin’s was the first major American war memorial to treat the dead as victims. The memorials at the World Trade Center, the Pentagon (also to 9/11; 2008), and Oklahoma City (2000) are of course victims’ memorials too. Needless to say, this genre readily engages design sensibilities of a puritanically reductionist, pathologically inartistic cast. As a result, features that would be minor or incidental or at most distracting in a traditional memorial assume major importance—the tactile value of inscribed names, say, or the effect of material finishes like the gloss on Lin’s wall that compels the visitor to see his own reflection. In the latter case the visitor gets to “reach out and touch somebody” in more ways than one.

Our minimalist antimonuments also can turn out to be astonishingly extravagant expressions of a visually impoverished culture. The World Trade Center memorial and museum will wind up costing many hundreds of millions of dollars both to build and to operate even though the living memory of 9/11 will fade, in the natural course of things, in a matter of decades, not centuries. The law of diminishing returns, along with the rule of common sense, has been turned on its head.

A monumental cenotaph could have endowed a less pharaonically scaled 9/11 memorial precinct at the World Trade Center site with the necessary symbolic focus. The design program could have accommodated the names of the dead, perhaps on the precinct’s perimeter. Remnants of the atrocity and other documentary material should have been relegated to an off-site venue for display to the public for as long as the public was interested. Finally, the twin-tower footprints should not have been retained. We needed a 9/11 memorial to embody a sense of national dignity as well as respect for the dead. Retaining the footprints helped set the stage for the narrow-gauge victims’ memorial we got.

If we take the trouble to learn from what Louis I. Kahn achieved, and didn’t achieve, at Four Freedoms Park, we might well conclude that his memorial would have better served FDR’s memory had its design been fully rather than marginally classical. The 9/11 Memorial in Lower Manhattan, on the other hand, serves as a very costly reminder that for every feat like the Vietnam memorial wall that seemingly defies the laws of artistic gravity, legions of memorials designed by people aspiring to be the next Maya Lin have all too conspicuously succumbed to them.

At least since the Renaissance and probably long before, Western civilization has placed a premium on originality in the arts of form. But as long as common sense is operative, originality is not taken to mean the creation of something unrelated to any precedent or prototype, but rather the reconfiguration of a given prototype in a vitally creative way, thereby endowing that prototype with new life and significance. A restoration of that sounder understanding of originality can only arise from a radical revaluation of our classical heritage and the rich treasury of forms it makes available to us for the commemoration of the men and women, events and ideals, that have contributed to the national welfare.

That revaluation has in fact been underway for several decades now, and as a result we are witnessing the gradual but steady growth of a classically oriented civic-art counterculture embracing architecture, urbanism, and fine art. That counterculture has now reached the stage where it should figure prominently in the selection of designers for our major memorials. To make sure that happens, the essentially political task at hand—one that should attract adherents from both sides of the aisle—is to curtail sharply the sway over our nation’s public art and architecture currently enjoyed by a modernist apparat deeply entrenched in government, cultural institutions, the academy, and the media.

For the biggest victim of the dominant trends in contemporary memorial design is the public itself. ♦

Catesby Leigh is at work on Monumental America.

Get the Collegiate Experience You Hunger For

Your time at college is too important to get a shallow education in which viewpoints are shut out and rigorous discussion is shut down.

Explore intellectual conservatism

Join a vibrant community of students and scholars

Defend your principles

Join the ISI community. Membership is free.

J.D. Vance on our Civilizational Crisis

J.D. Vance, venture capitalist and author of Hillbilly Elegy, speaks on the American Dream and our Civilizational Crisis....