J.D. Vance, venture capitalist and author of Hillbilly Elegy, speaks on the American Dream and our Civilizational Crisis....

Can Playing Prepare You for Living?

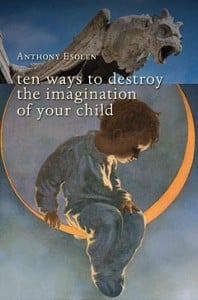

The following is an excerpt from the chapter “Never Leave Children to Themselves” of Anthony Esolen’s book, Ten Ways to Destroy the Imagination of Your Child.

When I was a kid, television had already marched like Sherman to the sea, cutting a wide swath through a child’s day, with hardly a twisted railroad track or a burnt barn to show for it. We still had some games, which we passed along to the younger kids when they grew old enough to play.

No grown up that I recall ever sat us down to teach us the rules. These were apparently invented and altered by kids from generations past—in some cases from centuries past: Hide and Seek, Red Rover, Dodgeball, Jump Rope, Cops and Robbers, King of the Hill, Jailbreak, Crack the Whip, Leap Frog, War. Some were improvisations of one of the recognized sports: Five Hundred, Home Run Derby, Hit the Bat, Pepper, Pickle (baseball); Horse (basketball); Two-Hand Touch (with delayed rushing the quarterback; football). Probably someone thirty or forty years older than I might remember ten times as many games. These constituted a thread of memory linking the ages. Now, let us all thank the totalitarian school and electronic entertainment, most of these games are forgotten. A former student of mine, a retrograde Eagle Scout, told me that his Boy Scouts lacked the capacity to get up a game of anything; they didn’t know how to organize themselves, and they didn’t know any games to play.

Or songs to sing. This too comes as a surprise, but children used also to sing, in the days before the specialization and compartmentalization of everything—and before the three-tone compression of popular music had left most of them so tone deaf that “Happy Birthday” sounds to them as complicated as Chopin. Even the schools cheerfully enough encouraged it.

The amiable reminiscer Harry Shute recalls his schoolmaster teaching the children “Annie Lyle,” “What’s the News,” “We Love to Sing Together,” and “Speed Away.” Laura Ingalls Wilder recalled how her father would of an evening take down his fiddle and play “The Arkansas Traveler” or “Sweet Betsy from Pike.” Thomas Howard has written of the natural virtues that such perennially remembered songs would encourage. Which virtues? Howard enumerates quite a few: innocence, duty, domestic contentment, fidelity, purity, soundness of mind, courtesy, sacrifice, joy, peace, plain goodness, and, most strange to us now, “hesitant delight in my lady”:

‘And ’twas from Aunt Dinah’s quilting party / I was seeing Nellie home.’ What the boy wants seems very restricted indeed: merely the delicate, nay fragile, venture of accompanying her to her door. The delight anticipated in such an austere pleasure puzzles imaginations cauterized by debauchery.

Philip Sidney in Apology for Poetry, affirming the power of poetry to move us to virtue, thinks first of all of ballads sung by the homeliest of peasants: “Certainly, I must confess mine own barbarousness; I never heard the old song of Percy and Douglas that I found not my heart moved more then with a trumpet; and yet it is sung but by some blind crowder, with no rougher voice then rude style.” At Saint Gregory’s Academy, a Catholic boys’ high school in Pennsylvania, everyone sings old ballads of courage and unshakeable friendship. “I shall never laugh again,” cries the refrain of one of the most haunting of them, mourning the loss of a comrade on the battlefield.

Not all such songs were taught in any formal way. I suspect that most of them the children picked up from overhearing their elders, or from other children. Some of them seem to have been made up by children, like the notorious song of Dunderbeck, coming out of New Orleans in the nineteenth century, and occasioned by a gruesome scandal:

Oh Dunderbeck, oh Dunderbeck, how could you be so mean,

To ever have invented the Sausage Meat Machine?

Now all the neighbors’ cats and dogs will never more be seen,

For they’ve been ground to Sausage Meat in Dunderbeck’s Machine.

Same thing for playing of musical instruments. Granted, many children learned how to play the piano or the violin by paid instruction. Most, however, did not: they could not, because there weren’t hundreds of thousands of music masters hanging about looking for work, and their parents hadn’t thousands of dollars to throw at them, either. So children learned to play music by watching, and hearing, and trying an instrument out for themselves: and this is attested to by accounts of people who played music but could not read it. The old Celtic fiddlers of Cape Breton did not read their thickets of arpeggios from a sheet. They heard them, remembered them, in their very arms and fingers, and passed along the memory to others who took up the instrument in turn. These things too formed no small part of a young person’s life. I don’t know who it was who invented the cigar-box banjo or the kazoo, either, but I’ll wager it was not Rachmaninoff.

We could go on in this vein for a long time. John J. Audubon roamed the woods as a lad and watched birds. He was a crack shot, and collected specimens. Many lads were crack shots. Some of these were taught by their fathers. Others taught themselves. Grownups did not take kids out for Slingshot Lessons. Maybe they taught them how to make a fish trap, or how to bait a line with a worm. Maybe they did not need to do that, because older brothers or neighbor kids had done the job already. Children collected butterflies, coins, stamps, arrowheads, feathers, rocks, and insects. They bought magazines and traded them with one another. They traded baseball cards. They played Rummy, Poker, Pinocchle, and Cribbage.

They mapped the woods. They learned bird calls. They foraged for nuts, and mushrooms, and berries. They jumped off bridges into streams. They rode freight trains. They needed no committees. They were alive.

Excerpted from Anthony Esolen’s book, Ten Ways to Destroy the Imagination of Your Child.

Excerpted from Anthony Esolen’s book, Ten Ways to Destroy the Imagination of Your Child.

Image by Herriest via Pixabay.

Get the Collegiate Experience You Hunger For

Your time at college is too important to get a shallow education in which viewpoints are shut out and rigorous discussion is shut down.

Explore intellectual conservatism

Join a vibrant community of students and scholars

Defend your principles

Join the ISI community. Membership is free.